My Powerboat Journey, part 2.

In part 1 of my Powerboat Journey, we looked at what it took to get to the RYA Advanced Powerboat course. Two years later, I finally managed to organise and take the exam to be able to get it commercially endorsed. This is a big milestone for me and it feels like a massive achievement – on par with my photography master or the boatbuilding diploma.

Prerequisites

There were a number of courses I needed in order to be able to take the commercial exam:

- Professional Practices & Responsibilities

- Sea Survival

- First Aid

- VHF

PP&R was an online course that, while put together quite well, was not the most exciting online course I’ve ever taken. But it was a good foundation for understanding the legal requirements for operating small vessels in a commercial context.

For the Sea Survival course, I chose to the RYA variant rather than SCTW, as the RYA one doesn’t expire. First Aid, I also did the RYA course, as that is accepted for the classes of vessels I expect to be operating.

I also needed a valid seafarer’s medical certificate. I opted for an ENG1 rather than the “easier” ML5, as I’m colour-blind, and the ML5 would be sent in for review. The doctor issuing the ENG1 can restrict it himself, so I am the proud owner of a medical certificate stating I am “Not fit for lookout duties at night.”

Organising an Exam

So, this is where it all went a bit pear-shaped. I’d been to see RibRide in November 2021 and expressed interest in working with them. We talked about doing some more training and organising an exam, but for whatever reasons, be it scheduling conflicts, personnel changes, miscommunication on both sides, and what have you, I didn’t manage to take an exam in the 2021/22 winter period.

As the exam has to be run at night, the next chance was going to be the 2022/23 winter season. Again, scheduling conflicts were an issue, but I also had a run of bad health from October 2022 through to February 2023 where I would have had no chance in passing a seafarer’s medical exam. I would have probably also had a hard time taking the exam, so another season went past without getting my commercial endorsement.

In the meantime, however, I had obtained my Powerboat Instructor qualification (more on that in a separate post) and after an onerous start in 2022, instructing took off in 2023 and got me out on the water for 5 courses and approx. 80 hours of instructing.

And this is the reason why I said at the beginning of the previous post that I don’t think it was a Bad Thing™ that it took me 2 years to organise and sit the exam: I gained so much experience just from teaching and participating in a number of training sessions organised by the RYA.

When I was taking my Yachmaster Theory course early November 2023 (again at Plas Menai, and a separate post will follow on that as well), I ran into Olly from RibRide and chatted to him about organising an exam. Everything fell into place, a week later we had an evening exercise session and then a week after that, the exam!

The Exam

Pre-Exam Preparation

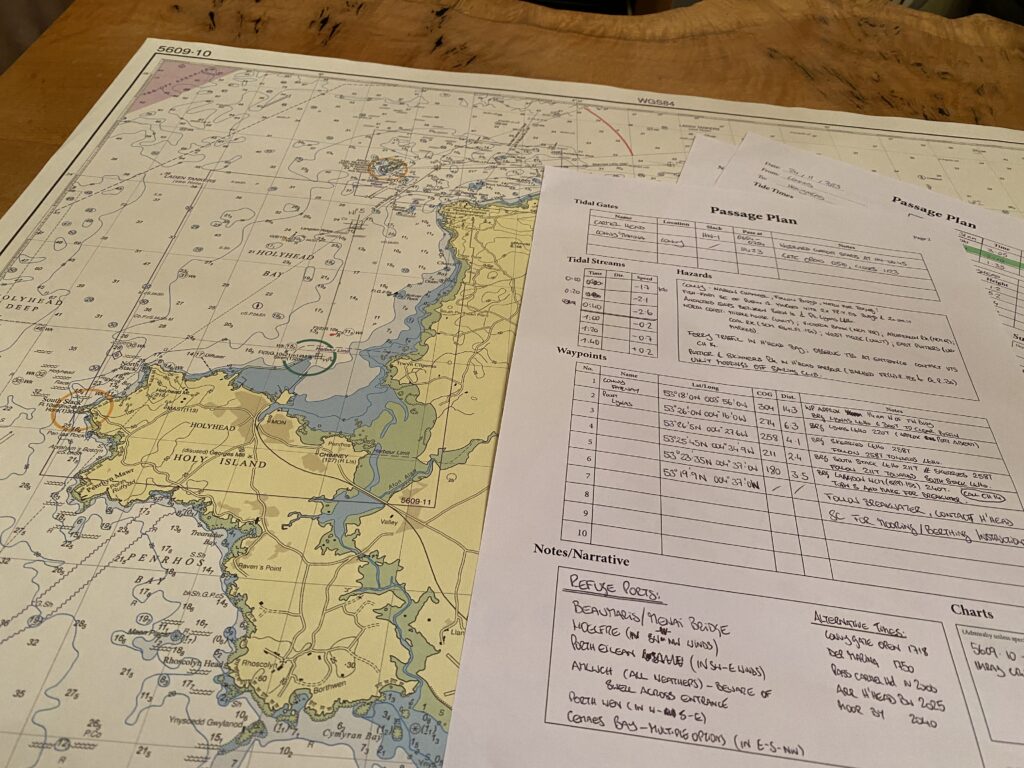

Part of the exam was to prepare a passage plan for a trip of approx. 60nm. Usually the examiner would pick a passage to plan, but I was given the message, “pick a passage of 30-60nm, use the tides of the day of the exam and assume favourable weather.” There’s any number of passages I could have come up with, but I decided to plan a trip from Conwy to Holyhead via the north coast of Anglesey. Working out the best time to leave was an interesting exercise and involved consulting the Cruising Guide, the Almanac, tide tables and lots of charts.

On the Day

Mark, the examiner, had requested we meet at RibRide at 1500. After the introductions, he let us know:

Don’t treat this like an exam, we’re just 3 blokes going out for a nice trip on the water this evening. That having been said, I do expect a certain level of professionalism, and the bad news is, this is a pass or fail exam, there is no in-between.

That may have been paraphrased, it’s been a while since the exam now, but that was more or less the gist of it. Mark then suggested that we do all the classroom/theory work before going out on the water and do the basic skills part and the navigation exercises all in one go (rather than doing the skills assessment, coming ashore for classroom and chartwork, and then going back out on the water).

He also laid out some of his expectations: safety first, good communication and his expectation that if he were to ask us at any point, we should know at all times where we are within 10-15m. No pressure then…

Passage Plan

The first part of the exam was to have a chat about the passage plan. I presented my marked up charts and written out passage plan, and talked through the decisions I’d made on routing and timing. Mark had some detailed questions about different parts of the plan, as well as asking some questions about chart symbols and what impact they may have on planning (for instance, the pilot boarding place off Pt. Lynas indicates that there may be large shipping and fast pilot boats in that area, so a good lookout will be required, etc.). I was then given the assignment for the evening’s trip: create a pilotage plan from Menai Bridge to an unmarked point on 10-Foot Bank.

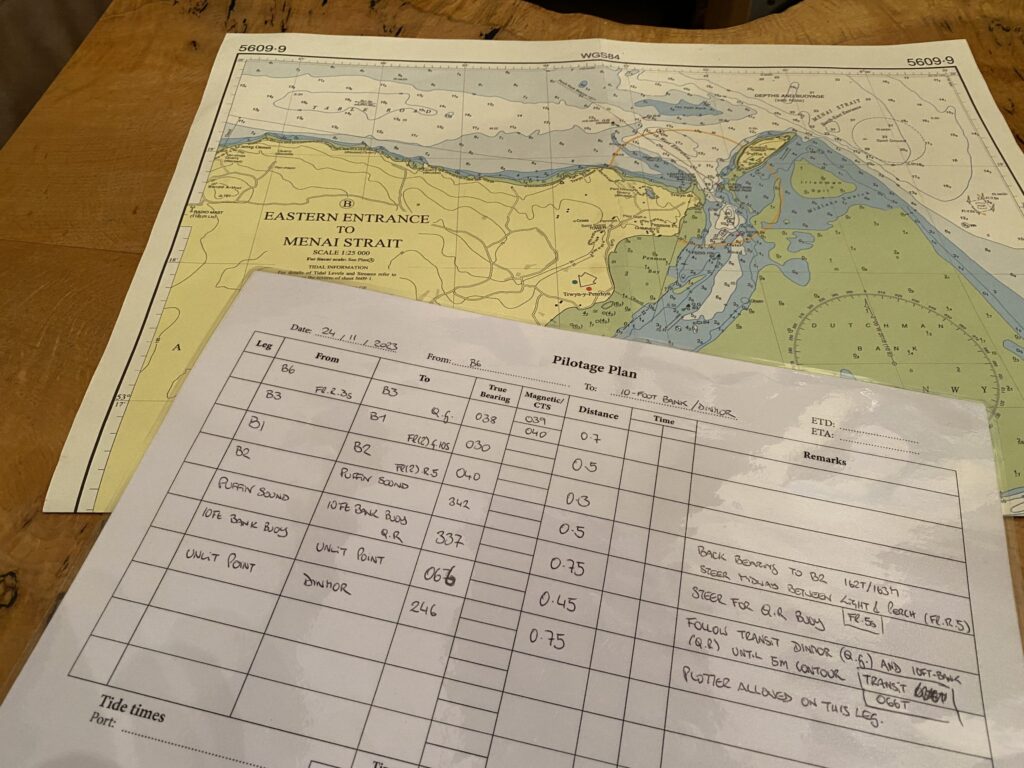

Pilotage Plan

I was allowed to use “all methods of navigation” (i.e. chart-plotter, etc.) to get to the B6 channel marker. From there, I had to use traditional navigation techniques only (i.e. compass bearings, distance run, etc.) to navigate the boat through Puffin Sound and from there to 10-Foot Bank and the unmarked point (the chart below shows the unmarked point and allows you to scroll around and zoom in). After finding the point, I was tasked to navigate the boat to the starboard-hand Dinmor channel marker, where I would hand over the navigation to Olly (exam partner Olly, not RibRide-Olly).

I already had a pilotage plan for most of the north-east end of the Menai Strai from previous navigation exercises, so I only needed to make detailed notes for the section where I was using traditional techniques, as well as making notes of the tidal heights in 15 minute increments. This part of the exam felt really easy, but only because it was something I had practiced many times before.

Skills Assessment

Once we had both sorted out our pilotage plans for the navigation exercise, we kitted up and RibRide-Olly drove us and the boat down to the slipway to launch. We took the boat out to a mooring buoy, and Mark asked us for two different safety briefings: one as if we had experienced crew on board, the second for passengers on a chartered trip. The sun had already set and the light was slowly going, but we did some basic boat-handling stuff, picking up moorings, coming alongside the pontoon, etc. This was all fairly straightforward, the current on St. George’s Pier wasn’t too tricky, and there was enough residual light (aka light pollution) from the land that picking up mooring buoys was almost as easy as doing it in daylight.

We tied up to St. George’s Pier, and while we were getting the boat ready for the navigation exercise, Mark asked us separately to join him on the back bench and showed us some flash-cards with light patterns and some weather charts. I initially thought a towing stern light was a trawler’s masthead light (green and yellow look very similar on a screen), but that confusion was quickly clarified. Once we were ready to go, we switched on the navigation lights, Olly started the engine, I cast off the lines, and away we went.

Navigation by Night

As I was navigating on the outbound leg, Olly was driving. We had already briefly discussed the pilotage, and with the notes I’d made, it was fairly easy to pick out the next buoy for each section. Somewhere before we passed Gallow’s Point, Mark threw Tracy (our Person-overboard buoy) over the side and called “Man overboard!“

Tracy had a light on, as all boaters should do at night, so she was easy to spot. The POB manouevre is something that we practice a lot, so stopping the boat, coming around and heading to pick up Tracy was nothing spectacular. As part of manouevre we send a MAYDAY distress call; when I mentioned I would send one, Mark said he didn’t need to hear the whole MAYDAY message, as he would assume that we know how to formulate the message. But he did ask, “What position would you give in the MAYDAY call?“

This one threw me for a moment, because I wasn’t sure if he was really asking for “about 1/4 mile south-west of Gallow’s Point, near channel marker B7” – which is the position I would have given in a MAYDAY call. It was definitely the correct answer, because we then had a discussion about why it doesn’t necessarily make sense to rattle off the string of Latitude and Longitude numbers – even if that is what is taught in VHF courses worldwide.

(The main reason is that in a distress situation, other vessels are required to assist. By giving a geographical reference, other vessels who hear the call who may be in the vicinity are far more likely to respond.)

We carried on with our course, bouncing off the channel markers until we reached B6, where I had to disable the chart plotter. To be honest, there wasn’t much difference in our navigation routine without the chart plotter, as visibility was good, the water was fairly calm, and we could spot the next buoys quite easily.

As we were coming up on B4 (which is unlit), Mark asked us, “there’s a buoy coming up on our starboard side. What colour and shape is it?” This was fairly typical for the rest of the exam, he would just drop innocuous questions about stuff – as long as he didn’t start following up the questions, I guess we got the answers right.

Nervous around Puffins

I was slightly apprehensive about navigating out through Puffin Sound. The year before, I had done a night navigation exercise, and failed to make it through the Sound because I wasn’t able to hold a back-bearing on the B2 channel marker. Without the pressure of the exam, in good visibility, it’s fairly easy to keep the light of the 10-Foot Bank channel marker off the port bow and aim for the centre-point between Penmon Light and Puffin Perch. But, as we were doing this properly, I had to hold a back-bearing in order to stay on our position line through the Sound.

The waves had picked up, we had about 1-1.5m swell, which was making the whole experience slightly uncomfortable. I lost the back-bearing and had to call for a stop. Mark queried the reason, I just explained that I needed to reset the position line – it didn’t help that the current was setting us off to port, so Olly couldn’t just steer on a compass bearing. I found the line again, and we powered on through. We didn’t run aground, but my nerves were a little bit shot.

Finding the unlit mark, in comparison was simple. We lined up Dinmor and 10-Foot Bank, and headed out on that transit until we reached the depth I’d calculated from the current tidal height (which I’d made a note of). Mark was happy, so we took the boat over to Dinmor by sight and I handed over command to Olly.

Bumpy Ride

I took over the helm, and Olly and I then had a quick discussion about his pilotage plan while we were bobbing around near Dinmor. Going back through the sound was a far nicer experience than coming out. Not being able to see the waves made for an interesting boat-handling exercise; luckily Rib 6 is a dream to handle and responds really well to any throttle inputs.

Once we were back through the sound, the waves diminished, until we had fairly flat water by the time we’d reached B6 again. Olly navigated us to his unlit mark, once he was satisfied, we started heading back towards Menai Bridge.

Glorious Night Out

This is the part of the exam I enjoyed the most. Cruising down the Strait at 20kts, 1/4 cloud cover, 90% moon, F1-2 wind and visibility for days. Mark stood up and positioned himself between the helm and navigator’s seats and started telling amusing stories about people who had failed the exam in spectacular fashion.

I did wonder why he was telling us these stories, but he was enjoying himself – as were we – and I think he was just making sure that we would still stay professional and in good control of the boat despite having a bit of a laugh. After all, the exam isn’t over until the boat is moored safely.

The ride back to Menai Bridge was uneventful. We did stop and have a chat with Beaumaris RNLI who were also out on a night exercise, but otherwise there was no traffic. Olly took over the helm to come alongside, and we put the boat to bed.

The Debrief

After we’d tidied up and made sure the boat wasn’t going to go anywhere after we left, we walked back to the base. At this point, I wasn’t sure I’d passed – I felt I’d made a right mess of the navigation out through the sound, so I wasn’t feeling super confident.

As we got back to the ready room, Mark asked if we didn’t mind doing a communal debrief rather than individual debriefs. At this point my mind started racing, because that meant we’d either both failed or both passed. As soon as we’d agreed, and before we’d even sat down, Mark came out with the best thing I’ve heard:

But I’ll put you out of your misery first, congratulations, you’ve both passed.

This was a great sense of relief, and the debrief was then extremely relaxed. I suspected we’d put too much pressure on ourselves, which Mark confirmed, but all in all, it was a very enjoyable, albeit challenging, night on the water.

My Conclusions

This is definitely one of the hardest exams I’ve taken. Not just the exam itself, but the multi-year build-up, and the other required courses – not to mention that all the knowledge gained in these course has to be completely internalised. It was nice to have it confirmed that I do know my stuff.

One of the positive aspects I took away from the prep day before the exam and the exam itself is how much my boat-handling has improved simply from teaching. When I teach a 2-day course, I may get 1 hour of driving over the 2 days. But the awareness of what the students are doing, the hypervigilance required to make sure we’re not going to hit anything, or inconvenience other traffic, etc. has just made so much of the driving become automated. I was surprised, but very pleased.

The best compliment I could have received though, came from a professional seafarer, who’s been going to sea – driving big ships – for over 50 years, in a brief WhatsApp exchange before I started the drive home:

Me: “it feels like a massive achievement”

My dad: “it is a big achievement … well done for persevering at it.”